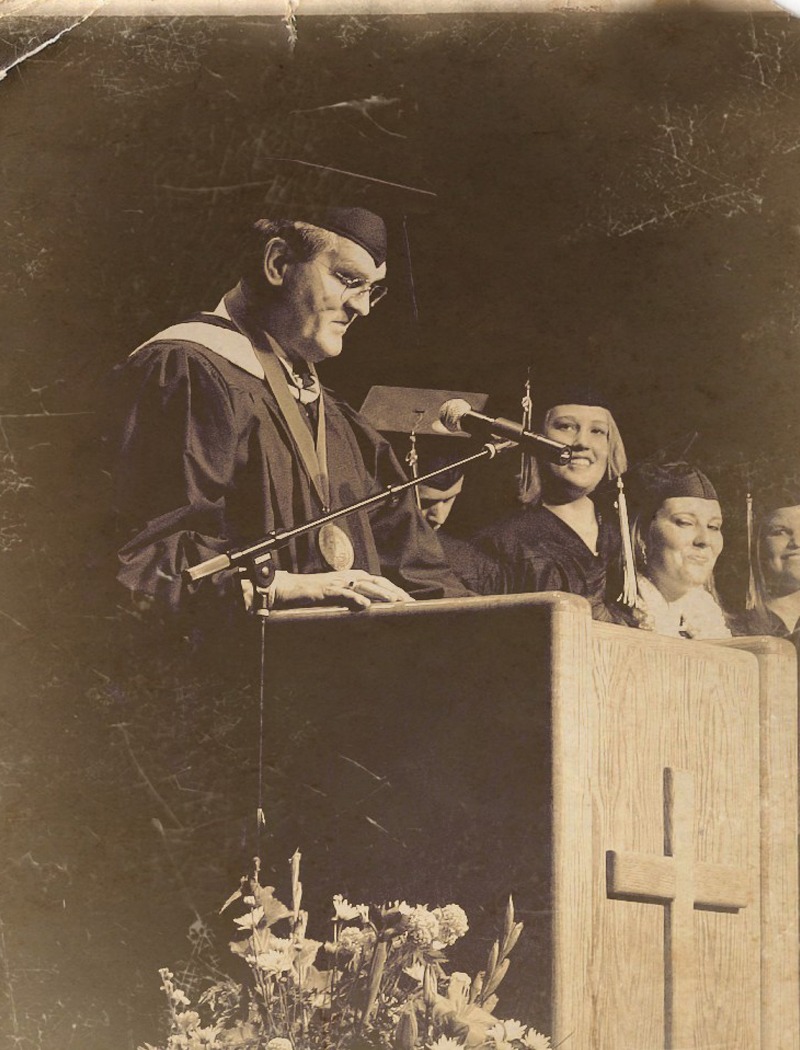

Dr. Matthew Peterson, Vice President of Education at Claremont Institute, was the commencement speaker at the 2019 Providence Christian College Commencement Ceremony. The following is a transcript of his address.

2019 COMMENCEMENT CEREMONY ADDRESS

WHO IS THE ELITE?

Christianity, Education, and America

Dr. Matthew Peterson

Claremont Institute

It is a great privilege to be here with you and to have the honor of speaking to you today.

Every once in a while I hear a story about a line from a commencement address that people actually remembered, as opposed to all the others that are quickly forgotten. But, when I set out to write this speech, I couldn’t even remember any of the supposedly memorable lines. So, I suppose as Abraham Lincoln said at Gettysburg, “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here.”

While you may not remember what we say here, I also suppose that each of you will never forget some part of your college experience. Over time, memory fades. But college, especially a small college at which you know everyone and everyone knows you, unites us in memory as we go on about our lives.

But we should also remember today that only one third of Americans over 25 have a college degree. So, in a way, you are all about to become “elites,” in the sense that you will now possess what most Americans do not have. You are each, as we say, “privileged.” Yet, to be called an “elite” today— to be called superior to others on account of your education— has a negative connotation and many Americans are understandably questioning the value of a college degree. Why?

The use of the word “elite” began to rise in the latter half of the 20th century after World War II, and it is now a common pejorative. Yet, as the poet and social critic T.S. Eliot noted in an essay in 1948, what he called the “Doctrine of Elites,” was met with the best intentions. Most Americans would still agree in principle that all positions in society should be occupied by those who are best fitted to their position.

The idea was that, as opposed to the injustices of racist or class-based societies, a large and democratic education system would identify potential talent, higher education would give the talented expert knowledge, and then they would be swept up into the positions in the world that they were best suited for. And if you think about it, most everyone would admit that our nation needs better leaders in nearly every area of our society. And any nation will ultimately perish if it cannot produce them.

So, whether we are talking about those who lead in the military or are venture capitalists educators or politicians or most importantly health families and churches, we want elites in place in the sense that we want people who are actually elite or excellent at their job. In other words, the problem isn’t the existence of elites. The problem is shaping the right kind of elites.

So, what is the problem with our elites? One problem that many say today is that they are corrupt. Corruption is a much broader notion than violating the law, although it certainly includes lawbreaking. Corruption is, as Aristotle pointed out over two millennia ago, occurs whenever people in power govern for their own sake and that of their back scratching pals, rather than for the sake of the common good of everybody else. And of course, corruption will always be with us as each of us, in our own hearts, are tempted to serve ourselves and our own unjustly at the expense of everyone else. And this is why every healthy society must continually and actively work to shape the structure of its civic institutions and culture to prevent its elites from becoming undeserving— from becoming corrupt.

Okay, so what should make our leaders qualified to lead us? What should college education give us, really? You see, T.S. Eliot worried that in our modern educational system our elites would be, “united only by their common interests and separated by everything else.” The modern elite, in other words, would not share ideas about human nature, character, or virtue, religion, or the most important questions human being have to answer to live a good life. Instead, Eliot worried that our modern elite would consist solely of individuals whose only common bond with each other was their professional interest.

And this is precisely the real fear of many Americans today. If education is just professional training, and if there is not a unified understanding of morality or religion, but in fact, a rejection of morality and religion, nor a unified elite culture educated to love and serve their communities and country, but in fact, a rejection of American principles and purpose, what is there to unite the elites except raw self interest? What is there to prevent them from putting their own good above the good of everybody else’s? From becoming snobbish and corrupt?

You see, college doesn’t just unify us through our social lives, as important and vital the relationships we make are, and as meaningful as the time you’ve all spent together was. It also unifies us in what we learned. The secret is that a college’s curriculum is a central source of student and national and theological unity. But this unity, above all else, is what is broken down in many colleges today.

As Allen Bloom wrote over 30 years ago in the closing of The American Mind, “When a student arrives at the University, he finds a bewildering variety of departments and a bewildering variety of courses and there is no official guidance, no university-wide agreement about what he or she should study.”

You see, our society today is unsure of, or in radical disagreement about, what education is and ought to be.

From what I have discerned, Providence Christian College provides a clear answer to this question. And this answer is discernible as similar to the answer that the early institutions of American education now known as “The Ivy League Schools” once provides during the period of the American founding—Classical, Christian, and American.

On commencement days just like this one in early America, colleges like Harvard and Yale would publish lists of ideas that graduates would have to publicly defend in order to graduate! Don’t worry you have it all easy today. These theses had been presented and debated in classes often in weekly disputations or arguments sometimes with the president of the university presiding.

Considering these lists of theses from long ago gives us insight, not only into what a graduate of the founding generation would be taught, but what united those institutions at their very core, what they thought education was all about. When you read these lists of things they had to be able to argue in order to graduate, the first thing you notice about what united those graduates two centuries ago is that they had a classical education.

In early American elite education’s purpose was in large part it create religious, educational, and political leaders. To do so, they took many required general classes and few if any electives, with ample readings in the classics. But not for historical or scholarly purposes. They thought that studying ancient literature, politics, and the history of human beings who came before them would prepare them for life. Now, today, we are tempted to say that that sounds very impractical. And, given the failure of very many colleges in this country, I think that’s an understandable fear. But back then they must’ve done something right. Writing documents like the Constitution of the United States and founding the country seems pretty practical to me.

Needless to say, over the last century and a half, things have changed at our Ivy League schools and pretty much everywhere else. There were some sensible reasons for these changes and certainly some of these changes have proven effective and useful. But what we were teaching elites for has become less clear. The content of education has changed as a new cast of managerial, scientific, and financial roles emerged over the last century.

So, Charles Eliot who was president of Harvard for 40 years from 1869-1909, introduced the elective system to Harvard undergraduate education and he transformed what was left of this required thread of centuries of western religious and classical liberal arts education for elites into the modern research university. And this led one historian to lament, “It’s a hard saying, but Mr. Elliot more than any other man, is responsible for the greatest educational crime of the century against American youth, depriving him of his classical heritage.”

This heritage was intended to be the basis upon which our nation’s leaders would be molded for lives led in service of their church and our nation. But as the shared understanding of the most important things eroded, what made on elite in America became increasingly less and less about the excellence of virtue, and more and more about the excellence or technical expertise. This change blurred the purpose— the shared purpose— of elite education.

So, consider what the graduates of Brown University had to be able to argue in 1770. “In order that one may perform the duties of life most faithfully, he ought to attend especially to the cultivation of his intelligence.” Or take Yale in 1797, “Without virtue and literature no republic can exist happy and free. In order that citizens may be gifted with virtue and intelligence, it is necessary that they should be instructed in letters and good morals. Therefore, such institutions being neglected a free and happy republic cannot exist.”

This classical education gave them insight into who and what we are, and how we ought to live our lives. For instance, they learned arguments that we have souls that are not merely bodily. “Matter cannot think, but mind can think, therefore the mind is not material,” they argued. “The soul does not come into existence from the physical contributions of the parents, but from God.” In fact, they thought the existence of God could be demonstrated or proven.

“Demonstration shows us the existence of God and the senses bear testimony to the existence of everything else. Reason and study,” they thought, “also gives us access to knowledge of what’s right and wrong.” They argued that, “The will of God, revealed by the light either of nature, or of sacred scripture, is an adequate rule and norm of conscience.”

In other words, they taught the principles of religion are in harmony with human nature. “Reason unfolded the laws of nature to mankind. The difference between good and evil, virtue and vice, set up by God, is immutable,” they argued, “Because it is founded on the nature of things. Thinking about nature uncovers the habits of behavior or virtues that lead to our happiness.” They thought that reason could tell if you thought about it that, “Prudence is the most difficult of virtues and justice is the mother of virtues.”

But reason alone was not enough. Their education was also unabashedly Christian. They required chapel attendance and group prayer. The top universities in America didn’t give up this practice until the early part of the last century. I mean, can you imagine telling everyone at Harvard they had to pray everyday, today? Even the first non-clergymen who became president of Yale in 1899 thought mandatory chapel attendance was necessary for campus unity, if nothing else. They argued, in order to graduate that, “The laws of vice and virtue are eternal and immutable and if a man aspires to true happiness, he must make his actions conform to the laws of God.”

In fact, one of the propositions said, “Death is rather to be undergone than any sin perpetrated. But philosophy, by itself,” they said, “can provide no stable and sure foundation of moral obligation. There was need of divine revelation for Christianity.”

They argued that, “On all matters, reasonableness marked the apostles, but human reason alone does not suffice to explain how the true religion was introduced and built up so firmly in the world. Human reason alone could not provide any means for man to secure future happiness and Holy Scripture preserved the knowledge of God among men.” In other words, “What we were painfully ignorant of both in this life, we are part of the city of God,” they thought, “as well as the city of man.”

Third, based on this classical Christian education, the Ivy League schools used to educate students about America and its purposes. “The common good is whatever leads to the true happiness of a society and in political life.” They said, “Whatever is opposed to the common good is also opposed to the law of nature.” They argued that, “All men are, by nature, equal, and the true equality of man is not a matter of science or honor or riches…” —Or going to college, I might add— “But the true equality of human beings is an equality of rights. Since,” they said, “To all men, by nature, liberty belongs equally. Therefore, every civil power owes its origin to the consent of people.”

In other words, the right of authority among men does not arise from any superior dignity of nature. Therefore even though the great evil of slavery was a stain on American life from the beginning, many of them argued upon graduation that, and this is another quote, “to reduce Africans to perpetual slavery agrees neither with divine nor human law.” In fact, they said that, “No civil law is just unless it agrees with the principles of the natural law,” a claim that Martin Luther King would go on to echo and bring to life long after they had all passed away.

So, I say to you today that you are not “elite” in the true sense just because you obtained a college degree. If you are “elite” in the true sense, it is because you graduate today from a school that is part of an American tradition of classical Christian excellence. Our so-called “elite” schools have largely abandoned that tradition. But each of you, in some way, stand in that tradition. You have now inherited that tradition. You will bring that understanding to your families, your communities, and your churches. And for that, I call you, “elite.”

Yet, I cannot end by puffing you up, sadly. The problem of our ruling class today is their arrogance and their surety that they are better than those they call, “deplorable.” This is why they are often abandoning American principles to silence dissent and force their will upon the rest of us. But America, because of Christianity, was based on a much humbler foundation then the tyrannical urges we see on all sides in the public square, today.

With the quiet confidence that faith did not necessarily conflict with reason and nature, America sought to allow for the freedom that conduces to virtue, justice, and the common good. Schools in early America thought, “The will of God accords perfectly with the happiness of society. But, no religion is rational,” they argued, “without liberty of conscience.”

As the scripture today reminds us, we do not live for ourselves alone, but for a loving God our families, our communities, and all those we are privileged to love, influence, or serve by leading. In so doing, we do not judge the souls of others as if we were God. We must not treat others with contempt for, as the scripture says, we will all stand before God’s judgment seat. Each of us will give an account of ourselves to God.

So, I end with an admonition, but also with hope. You start out wanting to change the world, maybe even fight the world, or conquer the world. In principle we all still do. In fact, many of us have changed or conquered the world in our own head. Perhaps, well, before breakfast while lying in bed in the infinitely expandable “if only” universes of our imagination. The imaginary changes we make in our dreams are often new and promising every morning and they seem imminently possible and right and just if only we were in charge.

But we often find were not in charge. And along the way you will discover, if you have not already, that it is much harder to incrementally change yourself in some small way by merely getting up from that same bed and getting out of your own head, that fighting for control of your own mind is often battle enough, that we each routinely fail to conquers ourselves, never mind the world.

It is a lifelong struggle to simply live a good life and be excellent in small ways in whatever circumstances we end up finding ourselves. And this is why we are ever in need of grace. And this is why you must draw throughout your lives from the faith and the love that was nurtured here. The faith that gives us hope. The limited understanding that ought to keep us humble.

May God bless each of you, your parents, your families. May God bless Providence Christian College. And may God use each of you to bless our country. It needs you. Thank you.

Dr. Matthew Peterson

Claremont Institute