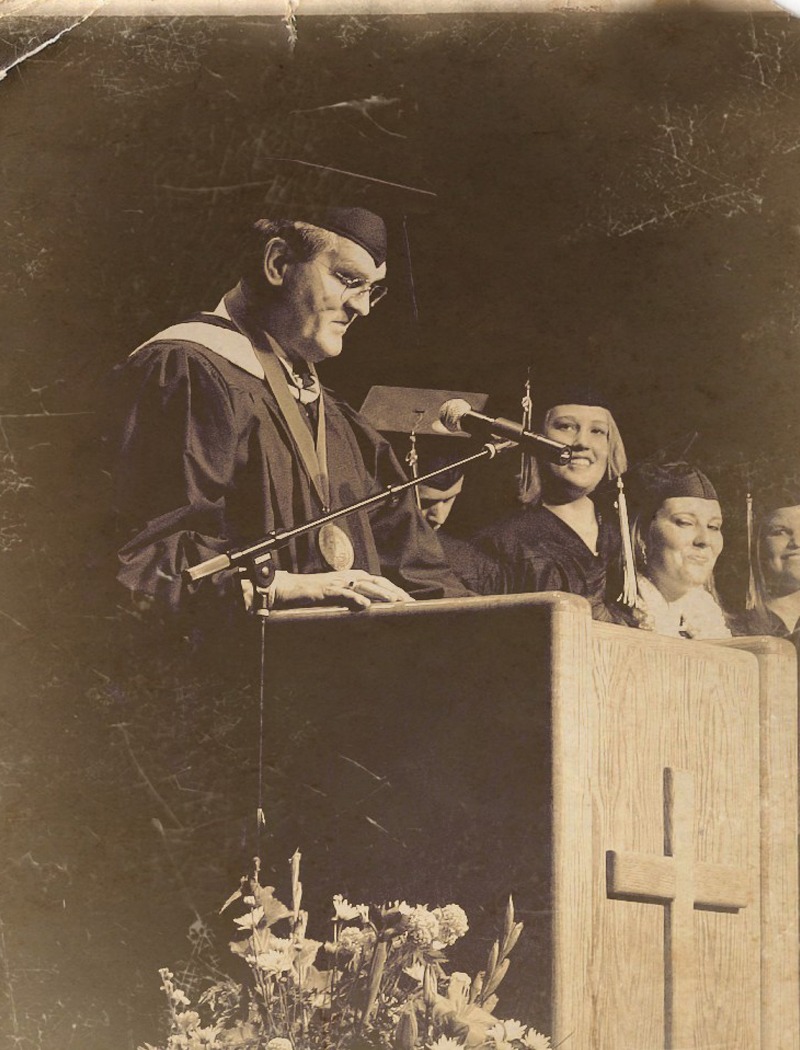

By Dr. W. Robert Godfrey

“I have revealed you to those whom you gave me out of the world. They were yours; you gave them to

me and they have obeyed your word. Now they know that everything you have given me comes from

you. For I gave them the words you gave me and they accepted them. They knew with certainty that I

came from you, and they believed that you sent me… Sanctify them by the truth; your word is truth.

As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world. For them I sanctify myself, that they

too may be truly sanctified.”

— John 17: 6-8, 17-19

In many Reformed churches, schools, and colleges, we take time at the end of October to remember and reflect on the Reformation. We recall the great work of God in renewing and purifying his church according to the Word of God. Already many are looking forward with eagerness to celebrating in 2017 the 500th anniversary of the public beginning of the Reformation, when Martin Luther—a relatively unknown monk and university professor—nailed 95 theses for academic debate to the church door in Wittenberg. By this action Luther unintentionally set in motion one of the most important developments in European and church history: the Protestant Reformation.

according to the Word of God. Already many are looking forward with eagerness to celebrating in 2017 the 500th anniversary of the public beginning of the Reformation, when Martin Luther—a relatively unknown monk and university professor—nailed 95 theses for academic debate to the church door in Wittenberg. By this action Luther unintentionally set in motion one of the most important developments in European and church history: the Protestant Reformation.

The anticipation of next year’s celebrations may leave us feeling that 2016 Reformation remembrances are completely overshadowed, and perhaps even irrelevant. Let me suggest that this should not be the case. Indeed, 2016 is a vitally important 500th anniversary in its own right. Certainly this anniversary is not as famous, but in its own way what happened in 1516 was just as significant as what happened in 1517.

In 1516, Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) published a critical Greek text and a new Latin translation of the New Testament. If you are not thrilled and deeply moved by my reminding you of this event, you should be. The publication of this New Testament marked both the culmination of decades of scholarly advances and the beginning of the Bible’s availability to direct the reform of the church. The Bible became again a vital, transforming influence in the lives of God’s people.

The medieval church had, of course, recognized the Bible as the Word of God. It had declared its inspiration, truthfulness, and authority. It had read the Bible in its church services and quoted it in its theological works. But in practical terms, the Bible had become muted and distant. Very few in the medieval western church knew Greek, the language of the New Testament, and so could not read it in the original language. Even if they had read Greek, few copies of the Greek New Testament would have been available even to scholars. The western church was dependent on Jerome’s Latin translation of the New Testament, which was one thousand years old in 1516. It had been a good translation for its day, but over time it came to be treated as if it were perfect. For common people, of course, Latin was as unknown as Greek. The Bible was not available to them in languages that they understood.

This situation began to change, particularly in the fifteenth century, because of a movement that came to be known as the Renaissance. Renaissance scholars became convinced that medieval learning had become bogged down and needed to be revitalized. They turned to ancient sources of western civilization, first to ancient Rome, and discovered a much more elegant and inspiring Latin than the Latin of the Middle Ages. Then they turned to ancient Greece, recovering a knowledge of Greek and of the great works of philosophy and theology written in Greek. In time they also recovered a knowledge of Hebrew so that they could read the Old Testament as well as the New Testament in the original languages. For these scholars, the truly educated person was a person who knew three languages: Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

In the early sixteenth century, Erasmus was the greatest of the Renaissance scholars living outside of Italy. He was not only very learned, but also very concerned about the moral corruption of the church. He believed that good books and education would help improve the spiritual lives of Christians individually and of the church as a whole.

In the providence of God, the Renaissance revival of learning took place at the same time that a great technological advance was invented in Europe. Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1396–1468) in the German city of Mainz developed a means of printing with moveable type. Books that once could only be laboriously copied by hand, one at a time, could now be printed much more easily, cheaply, and quickly. Between 1453 and 1455 Gutenberg printed the first Bible ever produced with this new technology.

Renaissance scholars used printing presses to disseminate their learning and to distribute ancient works long unknown. Erasmus, in addition to his many other publications, decided to prepare for printing a Greek text of the New Testament, along with a new Latin translation.

Erasmus knew that publishing a new translation of the New Testament would be controversial because many believed that Jerome’s translation was sacrosanct. Yet he believed that the church needed to study the Bible afresh. If Erasmus had not done this, other scholars would have and indeed did. But 1516 is the date when the Bible began to have a new life and power in the church. Erasmus could not have foreseen how explosive the presence of the Bible would be.

Two examples may illumine how Erasmus’s new translation could help people such as Luther think differently about the meaning of the Bible. In Jerome’s version of John 1:1, “In the beginning was the Word,” the “word” had been rendered with the Latin “verbum” which stressed the singularity and individuality of the word. Erasmus wanted to translate with the word “oratio” to stress the word as message, but “oratio” was a feminine noun, which seemed inappropriate for the eternal Son. He settled on “sermo” which almost means “In the beginning was the sermon.” Jerome had translated Matthew 4:17 as “do penance,” which had been used by medieval theologians as a proof text for the sacrament of penance. Erasmus rendered it more properly “repent,” which helped Luther rethink the character of the Gospel and of the sacraments. The Bible was being freed to begin reforming the church.

Jesus had prayed in John 17 about his Word in the life of his people. He declared to his Father, “I have given them the words that you gave me, and they have received them” (v. 8). He went on to pray, “Sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth” (v. 17). A central part of the ministry of Jesus was to give to the church the Word, and the function of the Word was to sanctify—that is, to consecrate and set apart as well as change—his people.

Before the Reformation, the Word for centuries had not been given faithfully to the people. As the Word was translated, printed, preached, and taught by Luther and the other reformers, the people of God once again became sanctified in the truth.

As we mark the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the return of the Word to the church, we must ask ourselves critical questions in light of John 17:8. There Jesus said that he had given the words of God and that his disciples had received them. In the Reformation, the Word was given and received. The spiritual test for us today is this: do we receive the words of God? The medieval church paid lip service to the Bible, but did not really know it or obey it. Many Protestants today seem to be in the same situation. Do we share the passion of Jesus, the early disciples, and the Reformers for the Word of God? Are we convinced that receiving the Word is the path to truth and life? Are we confident that the Word is all we need to serve God and experience his saving power? Let the Reformation anniversary of 2016 draw us all afresh to the Word of God.

Dr. W. Robert Godfrey is president and professor of church history of Westminster Seminary California. He taught previously at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Stanford University, and Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. He is the third president of Westminster Seminary California and is a minister in the United Reformed Churches in North America. He has spoken at many conferences including those sponsored by the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, the Philadelphia Conference on Reformed Theology, and Ligonier Ministries.

Dr. W. Robert Godfrey is president and professor of church history of Westminster Seminary California. He taught previously at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Stanford University, and Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. He is the third president of Westminster Seminary California and is a minister in the United Reformed Churches in North America. He has spoken at many conferences including those sponsored by the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, the Philadelphia Conference on Reformed Theology, and Ligonier Ministries.